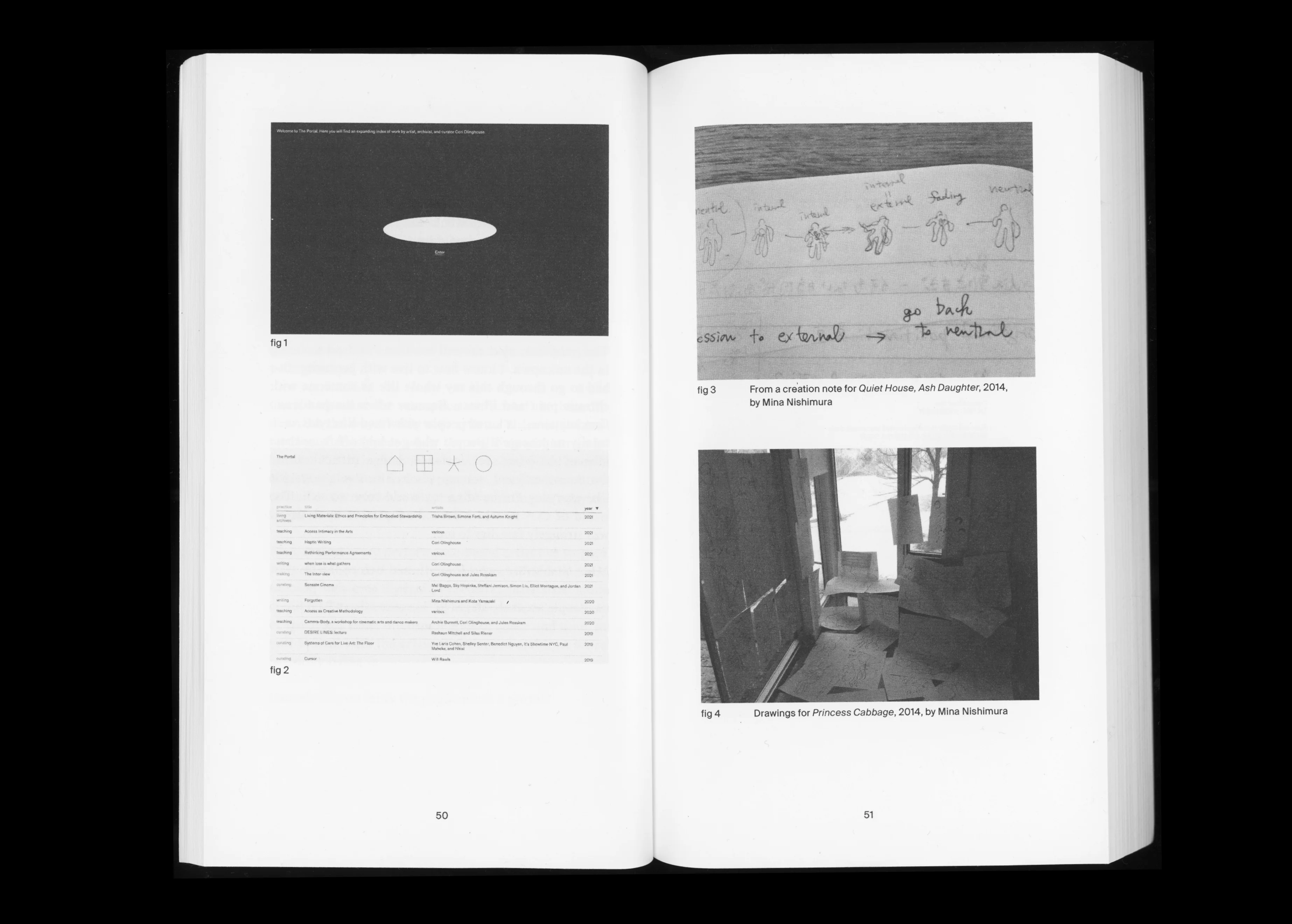

Laurel Schwulst: About a year ago now, we were working together on creating your website, The Portal — https://theportal.place.

The site begins with a dark, brilliant blue splash page with a small geometric drawing of a star reflected in a light elliptical pool (or maybe it’s a portal).

When you click to enter, you arrive at a tabular, textual index of projects. Categories appear on the left, each of which are color-coded. You see the word “writing” in magenta, “teaching” in dark blue, “making” in red, "curating” in cyan, and “living archives” in green.

The category “living archives” has always felt the most curious…

What does “living archive” mean to you?

Cori Olinghouse: I regularly work with dance and performance-based artists, and I’m interested in how their work interacts with archives and institutions. Many people associate archives with dead things, or the idea of preserving memory or holding onto the past. But performance is actually a living material, comprising peoples’ histories and memories and how these are viscerally held in their bodies.

In working with the materiality of memory, I consider my work a continuum. There is a past, present, future dimension to it.

Usually a performance is carried on through multiple iterations. Let’s say there was a particular work that was first staged in 1983. After the original performance, it may be performed several times later. And even if there’s an intention to reproduce or replicate it, there is absolutely no way live art can ever be perfectly replicated. There will always be inherent modulation in every iteration based on the new time and context.

I’m often trying to advocate for an artist’s practice and their embodied ways of knowing. And I try to insist structurally for ways that can show up in an archive.

I also work to ensure there are responsive, adaptive, and malleable structures in place so that an archive can be expanded upon in the future.

Laurel: How does an institution acquire a performance?

Cori: Good question. It’s a conceptual conundrum because you can’t acquire the “material” of a performance.

One worthwhile example is my collaboration with the artist Autumn Knight because The Studio Museum in Harlem (Studio Museum) recently acquired her performance, “WALL.” But usually the Studio Museum acquires physical works on paper, like photographs, drawings, or paintings. Acquiring a performance is something completely different altogether, so I acted as a linking bridge between the artist (Autumn) and the institution (the Studio Museum) to develop alternative ways of considering archives that hold living material.

Some institutions will actually absorb the rights to the performance. However, in working with Autumn, they decided it was essential that Autumn retain the rights to the work. So instead, the institution became the "stewards” of the work, or the caretakers of how the work is loaned out in the future. Which means that if another institution approaches the Studio Museum about staging or reimaginging “WALL,“ they must go through the Studio Museum.

Autumn and I collaborated on the documentation, and what materials another institution would receive if they stage the work. First, Autumn developed a series of scores that are open to interpretation that the future person (maybe they’re an organizer, curator, producer, artist, or yet to be identified person) would receive. They would also receive a budget (that lays out what the work requires) and an ethical outline (which is about how the Studio Museum expects them to care for the cast of Black femme participants).

And even though we also documented “WALL” in various ways, including through typical rehearsal and performance video footage, it’s extremely important to us that any future institution reinterpreting the work does not base their staging on this video documentation.

It’s important to Autumn that her performance “WALL” continues to have a life through its interpretation and translation. So it’s more about defining what the true identity of the work is, but in a very fluid way. We asked questions like: What are the elements that make “WALL” … “WALL?” And how can it change? So a lot of what I did was to map out elements of the work. For example, it needs “x number of people” or it “always needs people sitting in a line.” So we mapped out those details, while also giving space to how it could be interpreted anew in the future.

In becoming the stewards of the work, the Studio Museum is essentially acquiring the framework and understanding for what the performance is. And my role is to help build a living archive of the work that they retain as part of the acquisition file. This living archive helps them have contextual understanding on how to steward the work going forward.

Laurel: What are some specific techniques you use to build a living archive?

Cori: I often use the idea of “mnemonics,” which is about memory retrieval. I observe ways performance artists document their own practices. Sometimes they transmit their work in drawing or writing. But there is a way in which these drawings or writings trigger the senses. The documentation should act as a retrieval system for the five senses and the body’s nervous system at large.

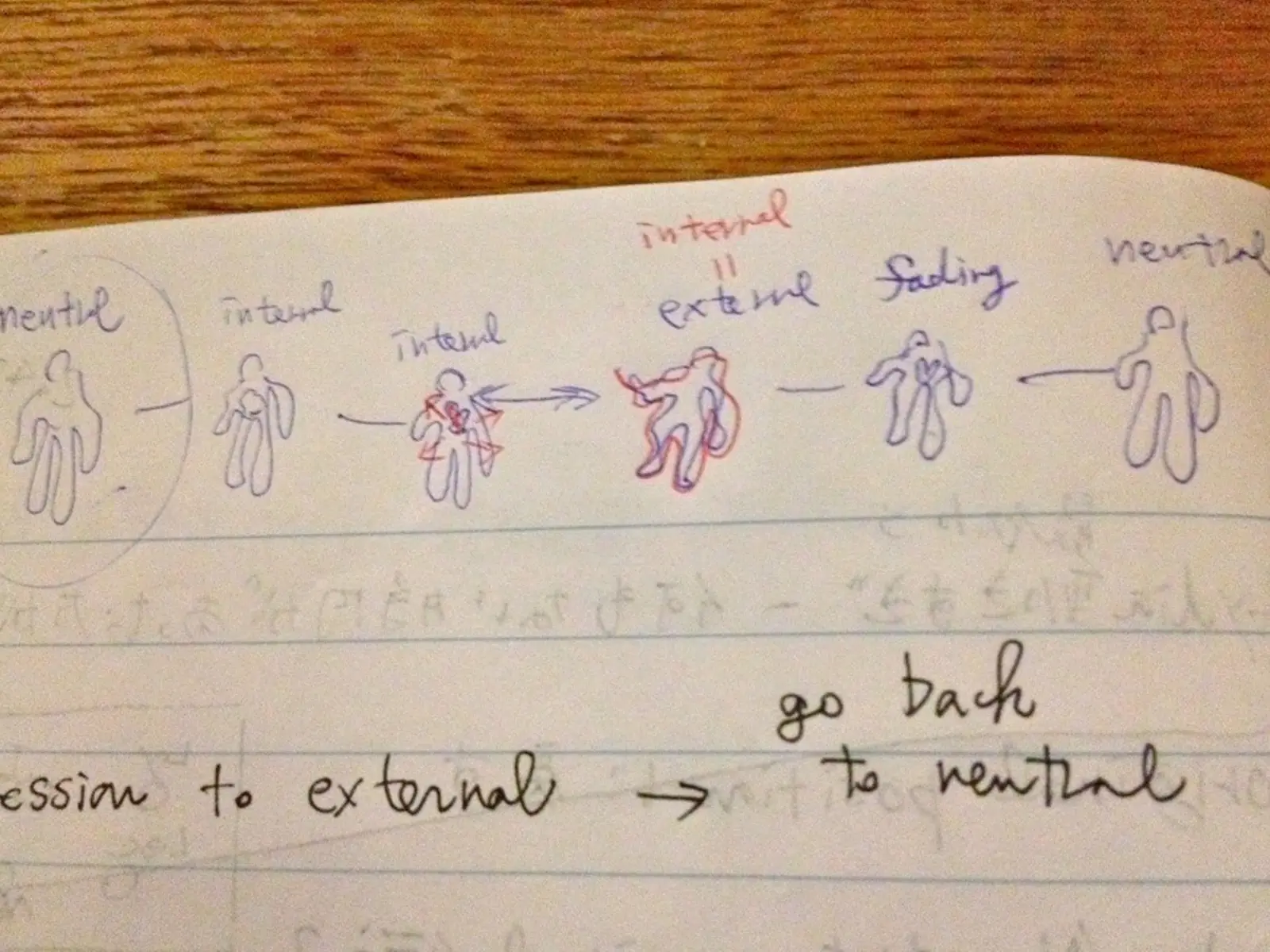

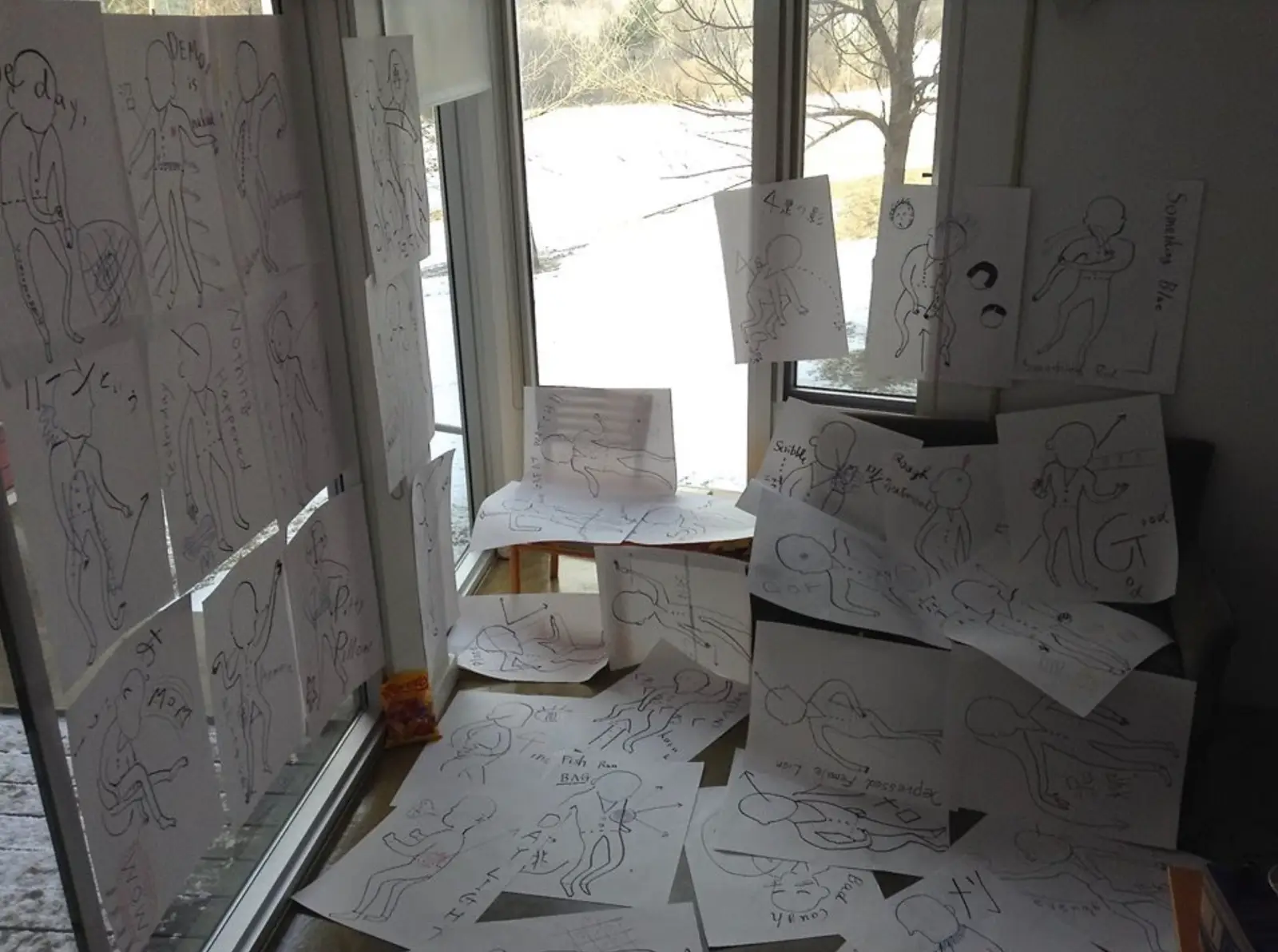

One dance artist I collaborate with, Mina Nishimura, has these beautiful drawings that describe what she calls “internal landscapes,” which are different characters that pass through the body. Her work, based in improvisation, comes loosely from a history of Butoh [a form of Japanese dance theater that began in the post-war 1960s].

Mina is from Tokyo, Japan and performs her work all over the world. When she does her work here, on the east coast of the United States, she often works with western performers who don’t have the same cultural competency or knowledge about lineages of Butoh. So her evocative, somatic, and sensory drawings and writing become another place of transmission.

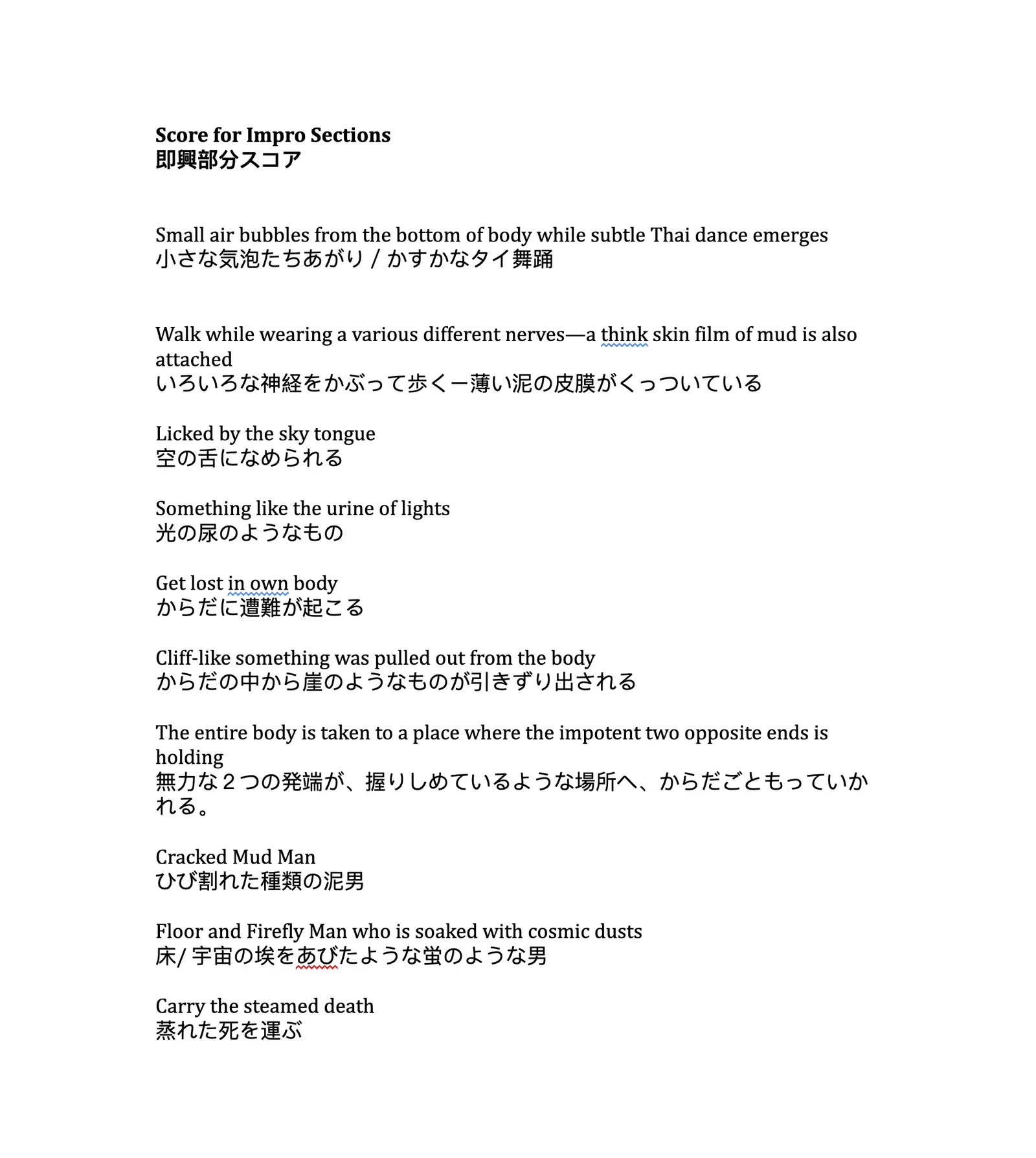

For example, this is a page in her notebook:

And here is a photo of many drawings, many “internal landscapes:”

In addition to drawing, language is another space I use as mnemonics.

Here is a written example from Mina. These are a string of images, or imaginative characters. They become a prompt or score for her own internal states, which she moves kaleidoscopically through.

With many of the dancers and choreographers I work with, I see them developing a shorthand to refer to something. Poetic names refer to enigmatic gestures. So instead of explaining what they’re doing, they have a poetic name for it.

For example, Mina often references a Butoh score that begins with, “A spider’s line pulls you front, a spider’s line pulls you back.” This writing is metaphoric, poetic, and enigmatic. Mina works a lot from Butoh-fu, or Butoh notation. These written images become a portal, or point of entry, which is the opposite of formal, mechanical, instructional information, which have no imaginative or open capacity.

I also worked as a dancer for many years with the Trisha Brown Dance Company. Like Mina, the writing in Trisha’s notebooks was also poetic and memorable. For example, some of her movements were given names such as, “Charlie Chaplin,” “Bee sting,” or “Haircut.” The nuance and imaginative capacity in these names literally changes the tone of the body. If you’re a performer trying to interpret mechanical language such as “the pelvis shifts, and the head rotates” that’s very different than entering into a state that’s like “Charlie Chaplin.”

When I build documentation with an artist, which is a lot of what I do, I’m not simply looking to document something in a standard way, like the way a gallery or theater would document an installation with photos or videos. Instead, I’m looking for the documentation that would carry the grammar of the form itself and its important sensory information, knowing that for people who transmit performance, those details mean something to peoples’ nervous systems.

Laurel: These sensory details in the documentation become, like you said, a portal, or a point of entry, to transmitting a performance.

I’m curious, how else does the word “portal” play into your practice?

Cori: I also use the metaphor of “portal” to broadly describe the way I work with artists. There is a transmission that happens when I’m working with an artist because I’m trying to hold some of the embodied knowledge that plays out in their practice. I’m like a memory container for whatever they’re transmitting or relaying to me.

Also, almost every performance-based artist I’ve worked with over the years uses the word “portal” in a specific way for their own distinct practice. The variation is incredible! These artists are trying to create other senses of space and time, or cosmologies of space and time, in part to deal with the crisis of the space and time we’re currently living in.

Laurel: Do you think the pandemic is a portal?

Cori: I think of portaling and portals as entering into the unknown. It’s about unknowing as a form of knowing.

Ideally the pandemic would be a portal. But we still need to unknow a lot of the habits we’ve accumulated from the old world into the new.

Mina Nishimura, who I mentioned before, talks a lot about “becoming otherwise” through her dance practices. In an ideal world, the pandemic encourages us to think in new ways and “become otherwise,” too.