It was a mysterious beginning, full of potential —

That is, I was invited to explore “egg” as an ongoing theme in my work and life, and I was feeling excited about the prospect.

Kristoffer suggested this topic to me. He has been a keen observer of my practice for a long time now, so I had some guesses as to why he encouraged me to focus on “egg.”

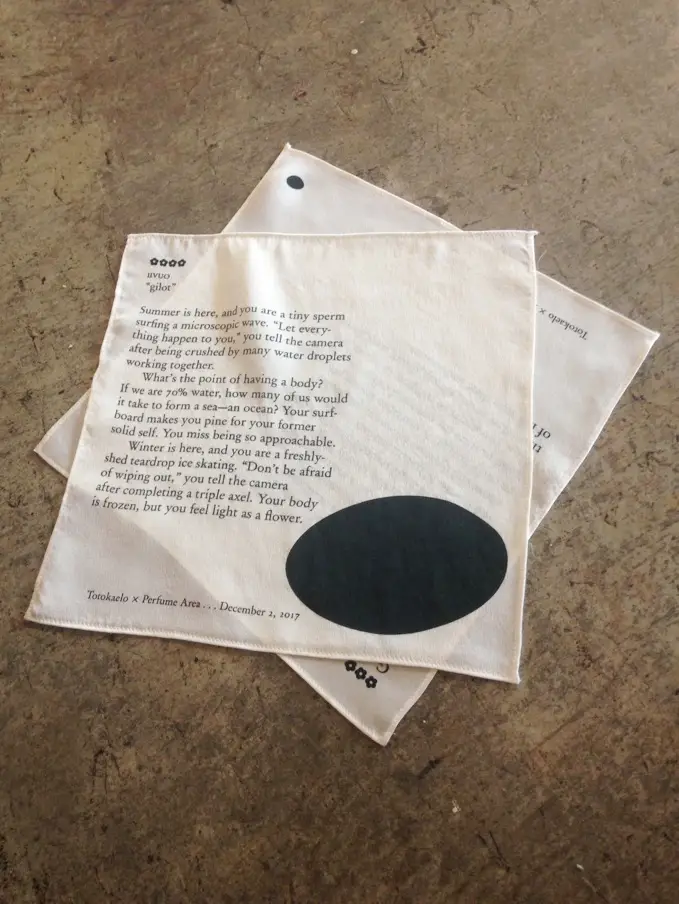

On a literal level, I hypothesized he’s been curious about my popular Are.na Channel — “Eggs in Art & Design.” Like its title suggests, it catalogs eggs that appear in works of art or design. I’ve cultivated this collection for the past decade, with the generous contributions of many others.

I also imagined Kristoffer might also sense this mysterious resonance between my life and “egg,” although maybe I was projecting.

By choosing my favorite items from my collection, I’m able to circle back and remember what it is about the egg that moves me. Honoring the egg means considering both the visible and invisible. Eggs are beautiful as a form, and I’ve realized that seeing them through art or design often allows us to appreciate them anew. Eggs are also mysterious, harboring potential energy. What is inside? What will emerge from the egg? Yet it’s important to remember eggs and their potential are nothing without the warmth of their mother, incubating them. Expanding from that, eggs are a metaphor for nurturing structures we provide others and sometimes ourselves, so we can get closer to some glowing, innate potential, excited to emerge.

Anyway, let’s begin.

I began my egg research by opening The Book of Symbols by ARAS, the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism. I found the page for “Egg” and read aloud:

The egg evokes the beginning, the simple, the source.✶✶

To start from a beginning, I was born in a town called Normal, Illinois. It’s a beautiful and simple place, with many flat prairies and cornfields nearby.

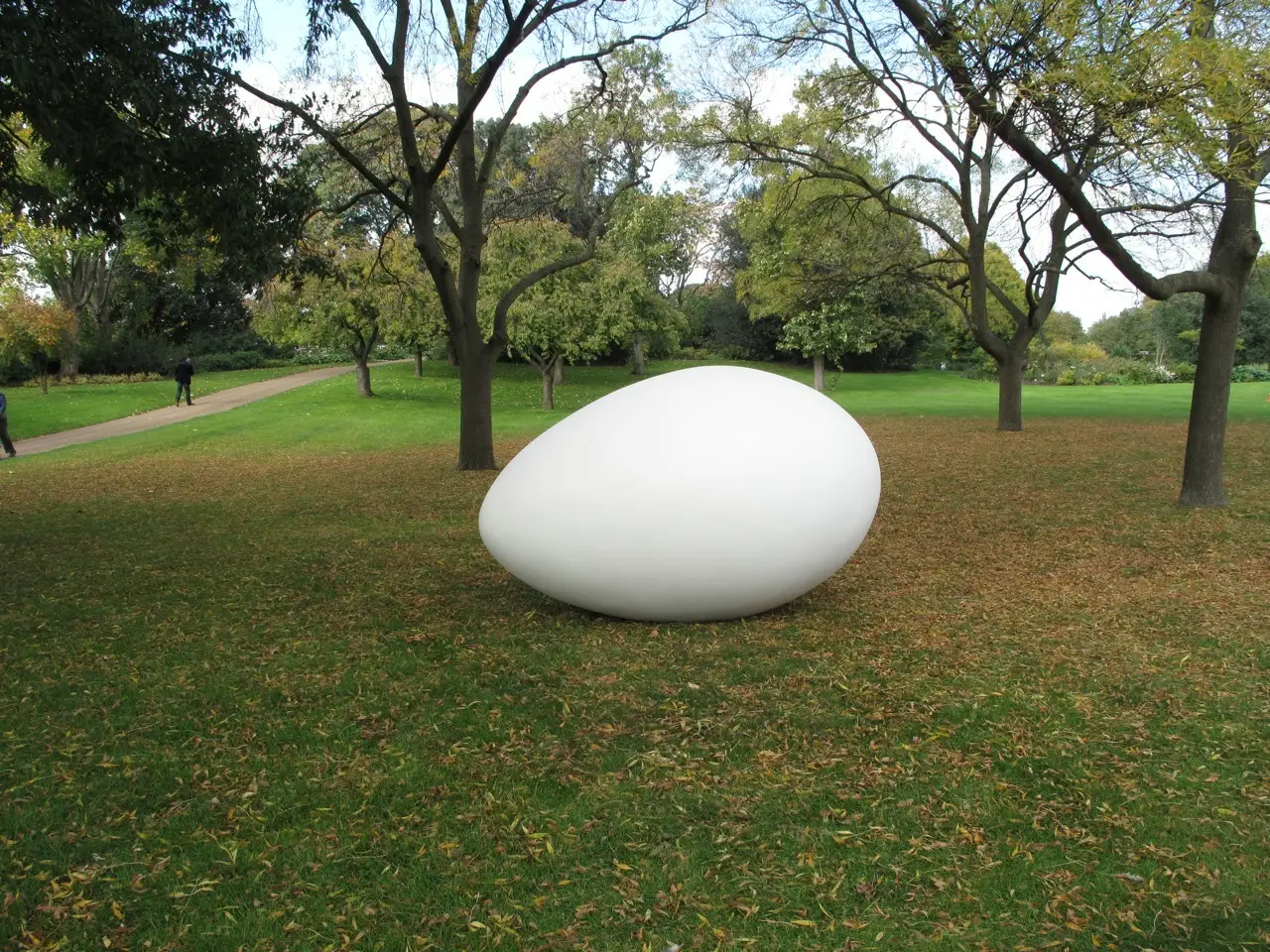

Eventually, I went away from Normal to art school, where I discovered the book Super Normal: Sensations of the Ordinary. The book catalogs design objects that are classics but also often anonymous, sharing that “super normal” is located beyond space and time, pointing to a future that has long since begun.

In particular, the authors (who are also designers) Naoto Fukasawa and Jasper Morrison mention the goose egg:

Seeing the goose egg, we are not surprised by the form at all, but the scale of it warps our perception momentarily, allowing us to see something normal in a new way. There’s nothing wrong with the form of a chicken egg except that we are used to seeing it. Seeing the goose egg, we can enjoy the form as if seeing it for the first time.✶✶

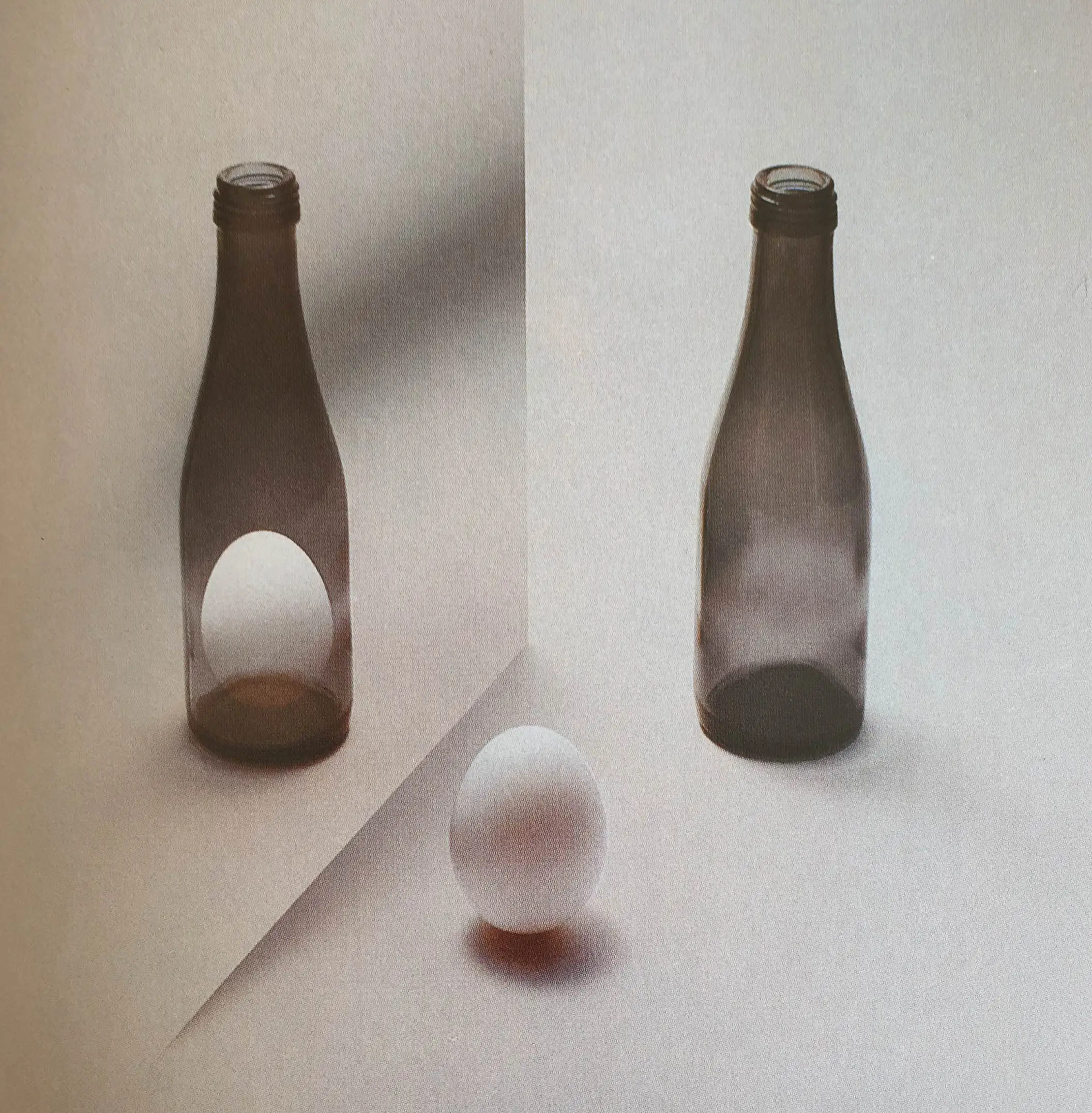

When artists use eggs in their work, I believe they are often simply pointing to the egg as a form so that you can also see it anew again, as if appreciating it for the first time.

In these pieces, I like the simple but profound moves artists make which help us appreciate something already amazing within our world.

Similarly, when I start new projects, I spend a lot of time understanding the context to see if simply by studying it, my work can bring to life or make more apparent something special already existing.

I returned to The Book of Symbols and continued reading the page for “Egg” —

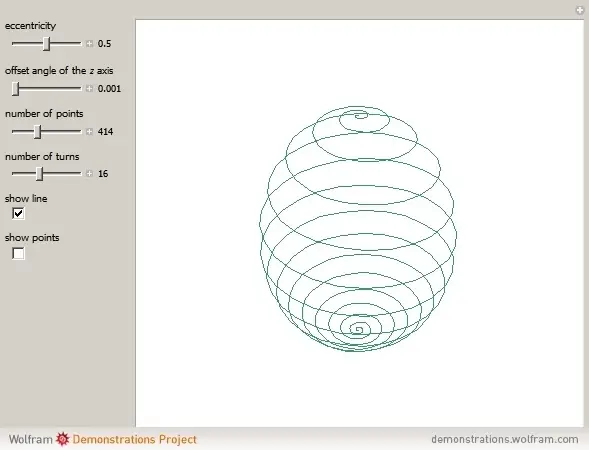

The egg is the mysterious “center” around which unconscious energies move in spiral-like evolutions, gradually bringing the vital substance to light.✶✶

I was reminded how eggs are about the mysterious and unknown.

Sometimes, we don’t know exactly what will emerge from the egg. We have no idea what kind of being will come to be when a new life first begins. Eggs harbor potential energy. Eggs are unfolding surprise.

In computer programming, an “easter egg” is a hidden or surprise feature —

The first easter egg in software took place in a 1980 video game called Adventure. Apparently, the company who made the game, Atari, did not include programmers’ names in the final game credits. To secretly include the credits, one of the game’s programmers covertly programmed some credits into the game. The credit only appears when a player moves over a specific tiny pixel called the “Gray Dot.”

Upon discovering the secret credit, Atari initially wanted to remove it. But after realizing it was too costly to remove, the company decided to encourage inclusion of hidden messages in future games, describing them enthusiastically as “easter eggs” for players to find.

Easter eggs also appear on websites. In my career as a web designer, I’m honored to have created many easter eggs by now — including special effects when you click a particular word or leave the site inactive for a couple minutes.

While website design and game design are related, game design is often much richer. Sometimes I wonder if I’m into eggs because of how much I played Pokémon game as a kid — and all Pokémon emerge from eggs. Even though I could have been a game designer, there’s something exciting to me about the everydayness of websites. Maybe some parts of everyday life should feel slightly game-like, involving well-placed surprises.

In 1885, the Russian tsar gave his wife a Fabergé egg. She enjoyed the egg so much that the tsar placed a standing order with Peter Carl Fabergé to create a new egg for his wife every Easter after, requiring only that each egg be unique and that it contain some kind of “surprise” within it.

Not too long ago, I wanted to “return to the egg” —

This impulse wasn’t about wanting more surprise or beauty in my life, however, but about desiring more protection to emerge anew.

In other words, I wanted my home to be an egg. I wanted to retreat into a cozy, protected, nurturing place again. While I knew this “egg home” I hoped to cultivate was mostly metaphorical, I also started to research literal egg-like houses and structures.

In the context of cultivating a home, eggs are about security. They also seem to be about a temporary period of incubation to hopefully emerge anew. But how do you both secure and incubate yourself? How do you generate your own loving warmth?

I turned to the “Egg” page of The Book of Symbols again —

Alchemy depicted the germ of the egg contained in the yolk as the “sun-point,” the infinitesimally small, invisible “dot” from which all being has its origin. It is also the creative “fire-point” within ourselves, the “soul in the midpoint of the heart,” the quintessence or golden germ “that is set in motion by the hen’s warmth” of our devoted attention.✶✶

How do you know when the container you’ve constructed around yourself is truly healthy and nurturing? When is a self-made sanctuary actually too protective? What constitutes a loving boundary, and when is that boundary actually cutting off necessary oxygen?

Literally speaking, avian and reptilian eggs are semipermeable to essential nutrients like oxygen. During the incubation process, the oxygen-permeability of avian eggshells in particular increases, to allow the new being to develop before it hatches.

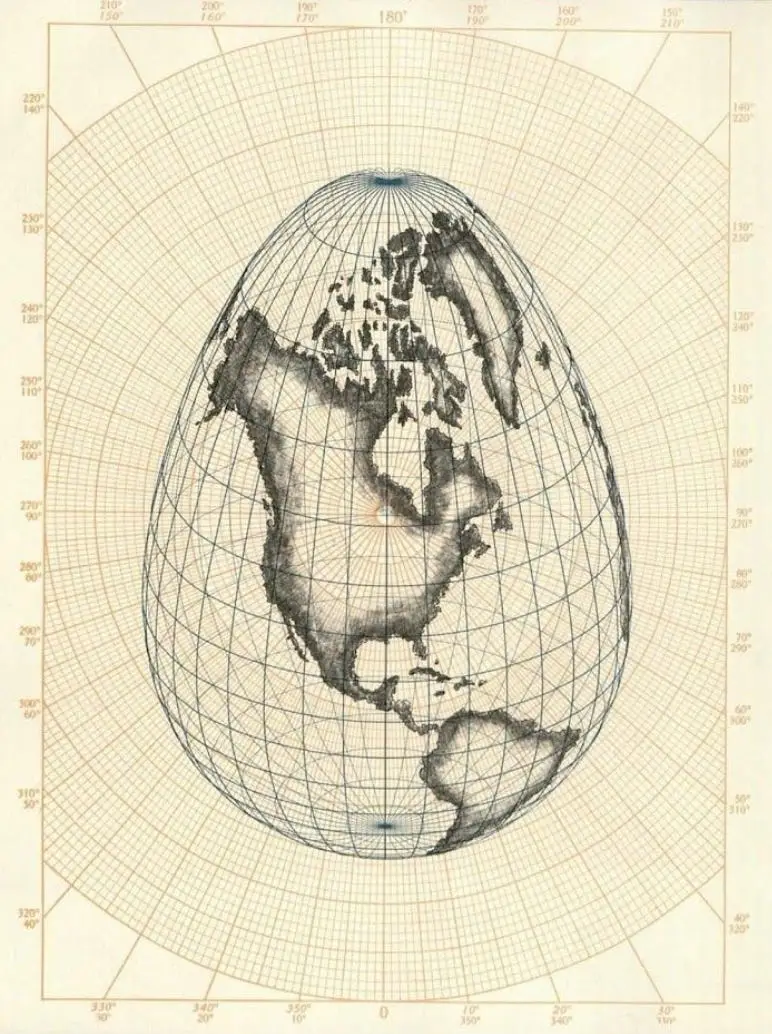

I was thinking recently how eggs and seeds are similar. But they are also different. Eggs honor the container (the nurturing process is mostly protected), whereas seeds are more a process (in collaboration with their environment, the soil). Eggs are contained, whole worlds. Eggs are universes unto themselves. Well, until they hatch…

In 2009, the Icelandic artist Sigurður Guðmundsson created the 34 very large eggs in honor of 34 species of birds that nest within the area of the installation.

Each granite egg depicts the shape and colors of the individual species of bird egg it represents. The eggs are all perched atop their own slabs of concrete, accompanied by an engraved plaque sharing the bird’s name.

I like how these eggs are beautiful contemplative objects, reminders to look more closely at the living world around us. These large eggs also stand on their own, quite literally, and can be appreciated simply as beautiful eggs first. Apparently the 34 concrete pillars were left behind from an old fish factory. The district manager of the town in Iceland called the artist Sigurður Guðmundsson to see if he had any ideas to repurpose the old pillars. Sigurður said this was the fastest large-scale artwork he’s ever created. I wonder if it happened so easily and so quickly because it was in easeful collaboration with something already existing.

In many creation myths, the universe is hatched from an egg. Often it is a bird, or birdlike deity, who lays this cosmic, world egg. Eggs are quite meta.

Carl Jung writes in The Red Book:

I.✶✶

Set the egg before you,

the God in his beginning.

And behold it.

And incubate it

with the magical warmth

of your gaze.

II.

And I am the egg

that surrounds

and nurtures

the seed of the God

in me.

Relatedly, my friend shared with me something they heard from a friend of theirs:

Apparently a female human fetus develops ovaries and eggs by the third trimester. That means that each of us was once an egg not only inside not our mothers, but nested inside our grandmothers too.

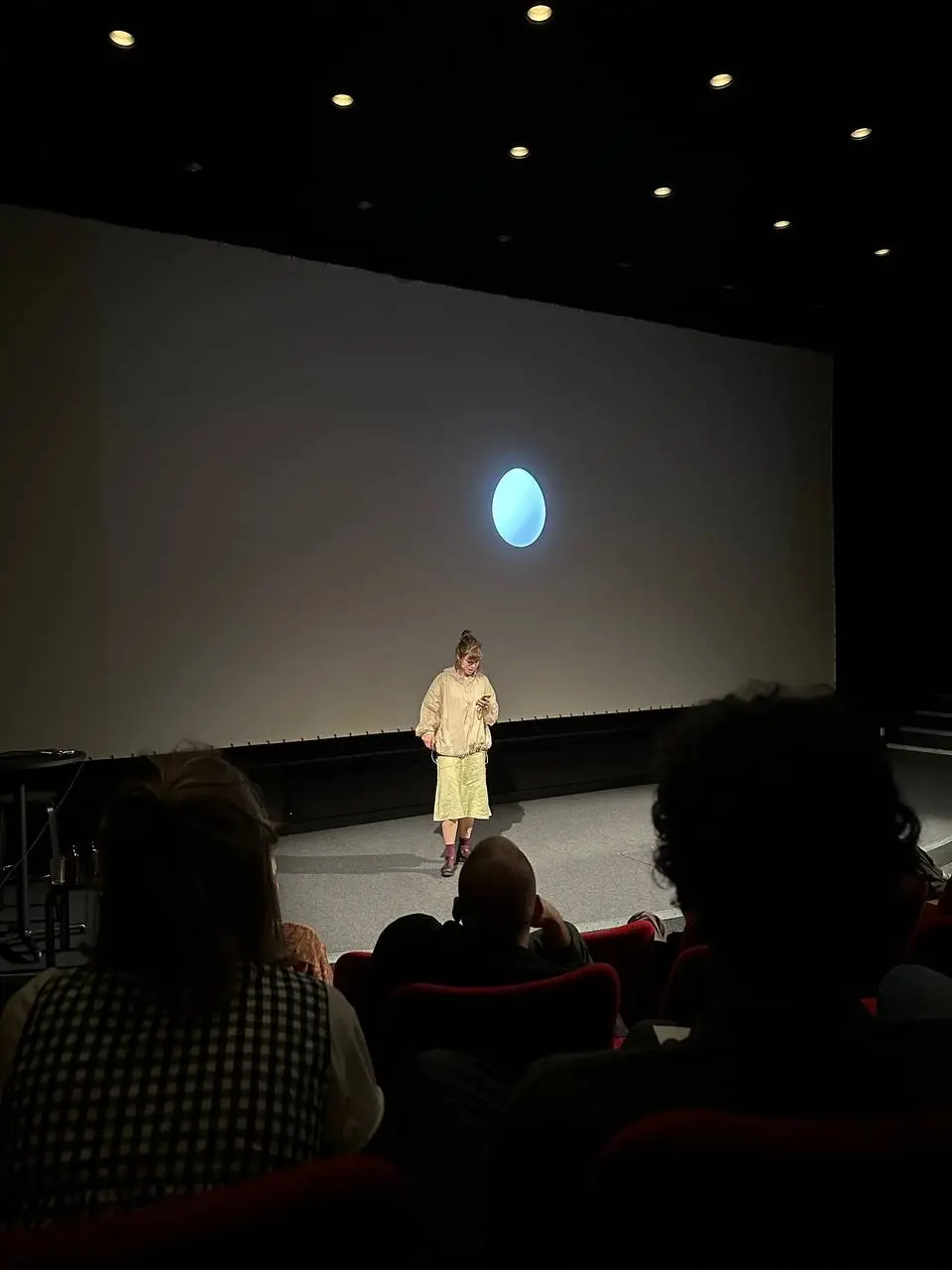

This “Egg Chapel” pictured above was commissioned to be one of the world’s smallest churches — a pilgrimage destination to hold small prayer and song services, baptisms, weddings, and musical performances — all inside an egg.

While this chapel is firmly on land, surprisingly it was built with wood by expert boat builders — as if it were a yacht.

A year ago, I proposed a special egg house with my friend. We began:

Imagine a large egg that’s actually a house.

It’s resting peacefully on its side in a golden wheat grass field in Nebraska. It’s often windy and sunny there — which is how the egg house gets its power — from its nearby wind turbine and solar panels.

The egg is wooden inside and feels like a boat — and that’s because it actually is a boat — built by an expert boat-builder.

Inside the egg, there is enough room for basic necessities for living: a single bed (that folds out to be double), a small kitchen, and a bathroom. There is a singular elliptical window near the top that frames the blue sky and lets light in, and a hanging paper lantern for reading at night. The "ribs" of the boat provide ample shelving and storage all around the egg, with numerous books (many about eggs and energy) available for reading.

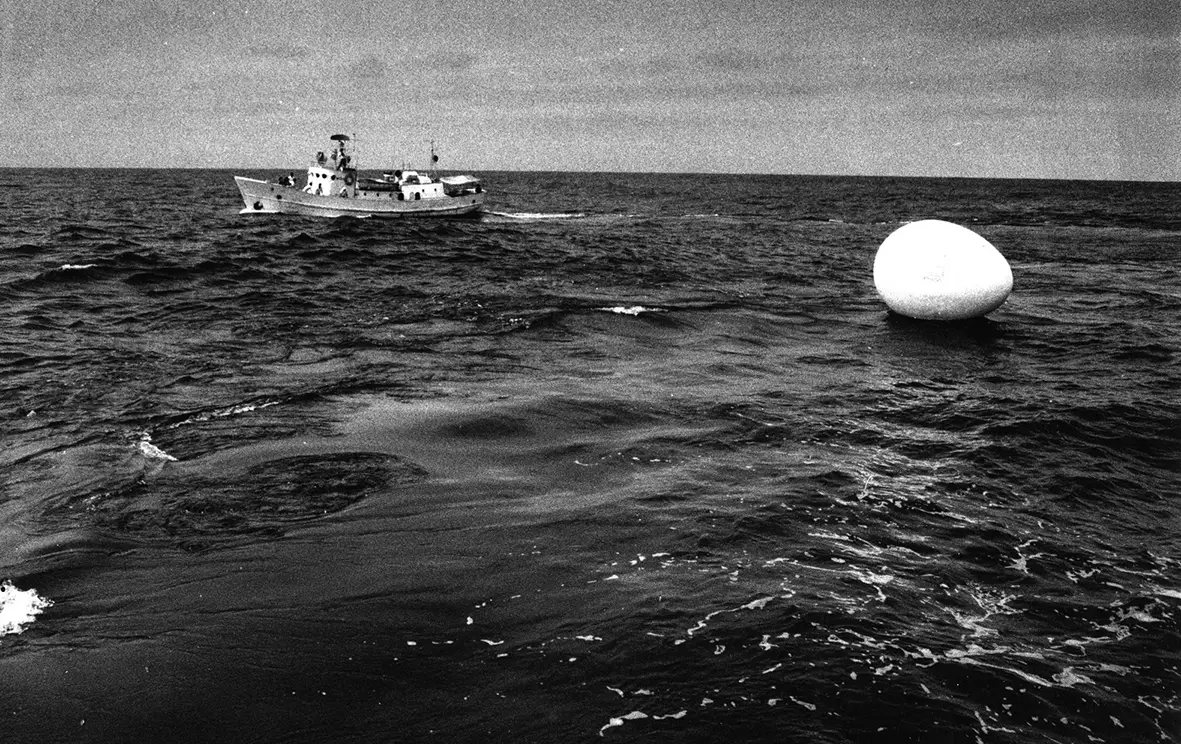

That’s because the egg is about potential energy. Surprisingly, this egg boat doesn’t swim but rests on land. Just like a real bird egg that incubates in a nest, gathering energy for its next flying phase, this egg house also harbors potential energy. When it’s time, it will evolve into its next form to take a voyage on water — an egg at sea!

This egg house is dedicated to forms of potential energy — wind & sun (that power the egg) and water (imagining the egg as a boat). A guestbook lets guests share their experience inside the egg and imagine the egg’s forthcoming voyage.

To re-enchant the egg feels powerful at this moment. Today more than ever, we need its patient, protected optimism.

For me, “egg” is most importantly a metaphor for nurturing structures we provide others and sometimes ourselves. It’s not always easy to create our own eggs, or self-nurturing containers. Studying eggs helps us create better ones in the future. Others might call it a support structure, as Édouard tweeted, “more often than not, the most meaningful human activity boils down to providing support structures for one another.”

If there is anything specific I learned from curating my collection of eggs and sharing these thoughts and anecdotes on them, it’s that the word “honor” is important to me. As I mentioned, I have this theory that when artists use eggs in their work, often they are simply honoring them. In other words, they are shining a light on the egg somehow: so that we can see it anew, as if for the first time.